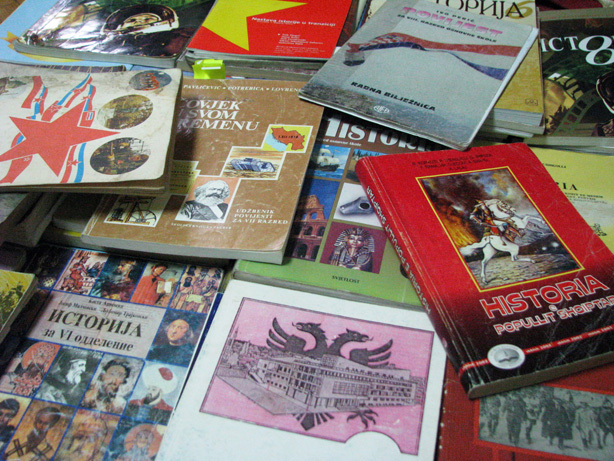

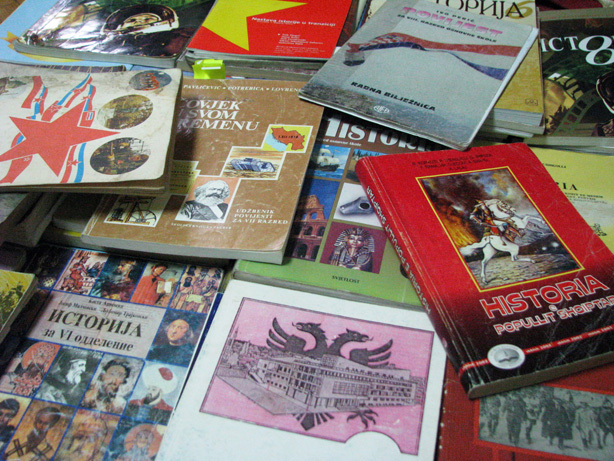

The Disputed Histories Library is a collection of text-books from primary and secondary schools, that have been in use in different time periods on the territory of ex-Yugoslavia. The purpose of starting this library by Vahida Ramujkic, was for it to be accessible to the general public, so as to inspire series of workshops, discussions and new projects. Until now it was available in Youth Center Crna Kuca in Novi Sad, on Spaport Bienalle in Banja Luka, in Knjizara of CZKD in Belgrade and in the NGBK Gallery in Berlin.

It turns out that students at schools in former Yugoslav countries learn histories that are quite different from those learnt by generations only few decades ago. In addition, these histories aren’t just different from the earlier ones, when there was just one version of history studied by everyone, a single “truth” that couldn’t be questioned or compared – now the histories of the newly formed countries offer a variety of “truths” on the way that certain historical events have taken place. Each one (of the countries descended from Yugoslavia) seems to have picked up the account of their rights in relation to the (re)constitution of the national state from their own particular point of view and the “true” explanation of what really happened.

Meanwhile, on the European continent, basically the opposite process is taking place in relation to the same issues – the formation and expansion of the Union of European countries towards Federalsim and economic and political power is inseperable from the need to adjust fundamental rules and principles of participating countries in relation to each other, and also the search for a new trans-national European identity based on citizenship.

We could say that in on the European continent we are bearing witness, in a way, to two opposite tendencies in politicial terms: a tendency towards uniting national countries and another to dismembering the federation to national entities. This logically leads to opposite tendencies, which will be used to conceive and form the collective identities of these different ideas of political systems. One will be oriented towards citizenship, the other towards nationality.

So, confronted with these processes of political reconstallations and reconfigurations of European states, which lead to the need to reconsider the collective identities (of its inhabitants) either as citizens or nationals, the idea of the official historic account requires revisions and modifications.

It’s more or less accepted that, to a certain extent, educational content is proofed by the current policies of the state of which they form part of the institutional architecture. In our culture, the moment when children start school is an initiation rite into society, where the future citizens of a particular state will be shaped. In reality it’s hard to say with any certainty how much of our own identity is generated as a result of our own relationship with our environment and our experience, and how much is due to a shared, collective identity that was engineered and imposed by current political doctrines. To what extent are the deciscions we make and the things we do our own, carried out in total liberty? And to what extent are they supplied by a broader national identity, without our awareness?

In short, there is a set of questions we can ask ourselves around these issues: How is the collective history of a people written, and what parameters are used? To what extent is there a description of real events, and in what way is it educated by the demands of the current state’s policy? To what extent is a national identity engineered and to what extent is it generated?

Do we really need to establish concensus on the existence of a single truth? Or, alternatively, can we can consider that the single truth doesn’t exist and that it cosists of different points of view in a “Rashomnic ” manner? And, finally, to what extent does the historical account, establishing a collective identity (natioinal or cititzen identity), play a part in the construction of our own personal identity, and end up affecting our personal histories?

More info at: http://www.irational.org/vahida/history/