When many people think of Croatia, if they think of it at all, they still picture a battle-scarred slice of erstwhile Yugoslavia.

Yet the Croatian War of Independence, which saw Croats face off against Serb-led forces, was 20 years ago. Now that Croatia has achieved sovereignty and returned to peace — the nation will join the European Union on July 1 — it is emerging as a hot spot for tourists eager to discover its stunning Dalmatian Coast and museum-packed capital.

Bordered by Slovenia and Hungary in the north, Serbia in the east, Bosnia and Herzegovina in the south and the Adriatic Sea on the west, this croissant-shaped country is impossible to digest in a single visit. We recently hit the highlights during a nine-day Abercrombie & Kent Connections tour called “Croatia: Jewel of the Coast.”

ZAGREB

Our first stop was Croatia’s capital, Zagreb, renowned for its cultural attractions.

Until July 7, the Klovicevi Dvori Gallery, one of nearly 70 galleries in the city, is hosting an exhibition of Picasso’s works, and more than two dozen museums are devoted to everything from archaeology and natural history to more unexpected finds.

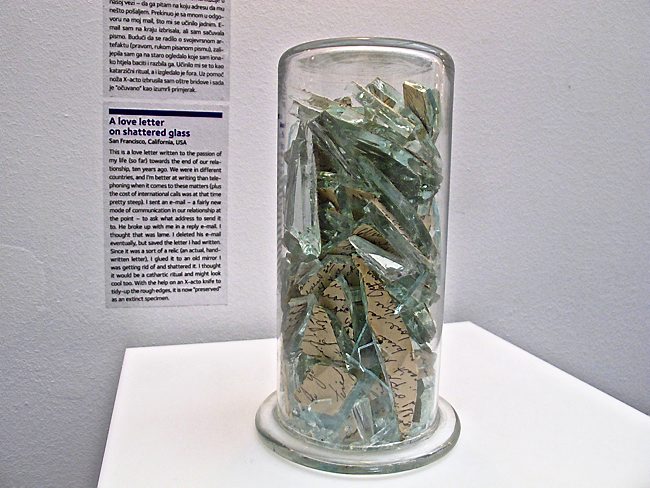

My favorite was the quirky Museum of Broken Relationships, a collection of alternately amusing and poignant mementos of failed affairs, including an “ex-axe” one spurned woman used to destroy her partner’s furniture, fuzzy handcuffs (ahem) and a can of “Lover’s Incense,” with this accompanying description: “Doesn’t work.”

With the city’s mixture of baroque architecture, cheerful tiled roofs and winding lanes, a visitor easily could spend a day wandering Zagreb’s streets.

On sunny afternoons, well-dressed denizens gossip over coffee along Tkalciceva. Women with tanned, weathered faces framed by kerchiefs sell fruit and vegetables in the Dolac Market, and religious folk flock to Stone Gate to light a candle and kneel before a portrait of the Virgin Mary, which survived a great fire in 1731 and is thought

to possess healing powers. St. Mark’s Church, with its peacock-colored tiled roof, may be featured on every tourist brochure, but according to local guide Valentina Buklijas, Stone Gate is where locals go for serious miraculous mojo.

SPLIT ON THE ADRIATIC

After two days in Zagreb, my group piled into a bus for the ride toward Split on the Adriatic, with a break for a hike alongside the teal-blue lakes and waterfalls of Plitivice National Park. Following a filling lunch of pork schnitzel, I found myself fighting off “carcolepsy” — the somnolent state brought on by long drives — as we passed bucolic farms, pine forests and hills unfurling toward the mountains.

But I was jolted to full consciousness by the sight of a tank parked

beside the ruins of a building. That, according to our driver, Drago Krsticevic, was a monument to “the war,” as the 1990s conflict is known here. As we continued, I noticed more crumbling, abandoned buildings, one spray-painted with a lone word: “Alamo.”

Attitudes about the war vary, but Krsticevic — a jovial, well-spoken young man — displayed a remarkably evenhanded view.

“I don’t have anything against normal Serbs,” he said, meaning those who aren’t militant. “The younger generation not born during the war is fed up with this idea of hate. We must look in the future; we shouldn’t look in the past.”

Arriving in Split, a coastal resort community at the foot of stony mountains, the comingling of past and present was baldly evident in the architecture.

On the outskirts, tall, monolithic apartment buildings — erected under Yugoslavia’s post-World War II communist leadership — dominate the skyline.

But nestled on the Adriatic, the ancient Roman Diocletian’s Palace dates back to around 300 A.D.

The palace is not only an historic monument but also a compact walled city where people still live and work. As the heart of Split, it is filled with shops, restaurants, bars, apartments and laundry lines strewn like bunting across alleyways.

“Within the palace, you can see Egyptian columns from Luxor, Roman arches, Gothic palaces and 18th-century Baroque balconies,” said our guide, Mislav Luketin, a witty, wiry fellow with the indefatigable energy of a Jack Russell terrier. “When I see a satellite dish on a Roman wall …” he kisses his fingertips to express his appreciation. “What I love is that life goes on.”

BRAC

To experience a slightly slower pace, we took a 50-minute ferry ride from Split to the island of Brac, best known for the pebbled beach of Zlatni Rat and the quarry that produced the bright white limestone used to build the White House.

Our driver Krsticevic skillfully navigated through stone villages that cling to rocky slopes, past olive groves and vineyards planted in private gardens. But the most memorable part of our visit was a lengthy lunch at Kanoba Toni, where three generations of gentlemen, each with the lantern-jawed good looks of a movie star, served us heaping portions of lamb and fresh seafood and copious amounts of delicious house wine.

DUBROVNIK

Our movable feast continued on our drive toward Dubrovnik, a UNESCO world heritage site and arguably Croatia’s most famous tourist destination.

On the way, we paused for a wine tasting in Trstenik at the birthplace of Mike Grgic, who opened this offshoot of his California-based Grgich Hills Estate winery in 1996, and lunch of oysters and mussels plucked directly from the sea at Bota Sare in Ston.

Physically, I was satiated, but I was thirsting for my first view of Dubrovnik, which George Bernard Shaw once proclaimed “Paradise on Earth.”

A walk along its medieval walls, which stretch for more than one mile, was a must. From atop the ramparts, I could can gaze directly down into the Adriatic to the south, into the harbor to the east and over the red-tiled roofs and domed churches inland.

It might look familiar to fans of HBO’s “Game of Thrones,” which adopted Dubrovnik as a stand-in for King’s Landing in the second season.

During the war in the 1990s, the world watched in horror as this splendid city was shelled by Serbian and Montenegrin forces from the Yugoslav army.

Tea Batinic, a local gallery owner, describes those dark days. Her attic was hit by five shells, buildings were burning all around town, and the city was without power or water. Batinic conjured the memory of a huge storm that brought rain “like a blessing from heaven” and gratefully recalled how neighbors found letters from her family, which were scattered when her home was damaged, and saved them for her.

The only time this strong, feisty woman came close to tears was when she described seeing a shell strike the Gundelic Square fountain, which she remembered “from childhood, before I could even touch the bowl.”

Today, the fountain is fully repaired, and the buzzing square is filled with vendors hawking fresh produce, folks sipping pale pints of beer, and pigeons awaiting a man who comes along to feed them every day at noon.

The city has been restored to its glory, with only a few shrapnel pockmarks visible on its walls and stone pavements,.

Under the skin, scars may always remain for those who remember the war, but, as they say, life does indeed go on.

Source: twincities.com