During the Third Reich, Turkey provided refuge for Jewish intellectuals. Today the Jewish community is rapidly shrinking, but those who are left can recall a long tradition of Jewish culture in the country.

Izzet Keribar is looking out the window. “On Sundays they used to raise the swastika flag here at the German consulate; I could see it from my bed. It was like in German films, with the Gestapo and their headquarters.”

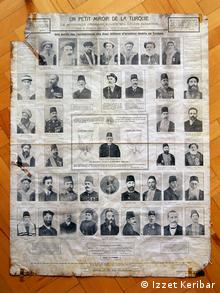

For the first time in decades, Keribar has entered the house in which he was born in 1936, close to Taksim Square, in the heart of Istanbul. Today, Keribar is an internationally active photographer and has exhibited his work in Germany and elsewhere.

The German building still stands diagonally across from the house where Keribar spent the first 20 years of his life. Today, it is the General Consulate of Germany.

“Back then, the embassy didn’t bother us,” he says. “We didn’t know what happened in the Warsaw ghetto, in the concentration camps in Dachau, in Majdanek and Auschwitz. When I was 11, 12 years old, we gradually became aware of what really happened during the war.”

Then he adds, “I daren’t even think about what would have happened if we, as Jews, had lived in Europe!”

Refuge in Turkey

Turkeywas a relatively safe place during the Third Reich – not only for those Jews like the Keribar family, which had lived there for generations. Émigrés from German-speaking regions also found refuge there, mainly intellectuals and academics.

As specialists, they were in demand in the young Turkish republic. Founded in 1923, it was desperately in need of skilled workers to build the state and universities based on the Western model.

During the Third Reich, 69 Jews from Germany and Austria occupied high-ranking positions in Turkey as professors or state advisors. Others worked as lecturers or assistants.

Together with their families who came to join them, between between 500 and 600 Jews found legal exile in Turkey. Among them were prominent figures such as lawyer Ernst Eduard Hirsch who significantly influenced the judicial system in Turkey, financial theorist Fritz Neumark, as well as literature professors Erich Auerbach and Leo Spitzer.

Over time, a top German university was created in Istanbul with revolutionary seminars and readings, even on the issue of sexuality.

Jews or Zen Buddhists

The historical significance of the intake of persecuted Jewish intellectuals in Turkey is still a contentious issue.

“I have thought very hard about that,” says Robert Schild, who was born in Istanbul in 1950, the son of Austrian-Jewish parents who had lived in Turkey for three generations. “The whole fuss about the German intellectuals is a fad. Twenty years ago, people were hardly aware of it.”

The economist, theater critic, author and long-time columnist for the “Salom” newspaper, has taken a critical view of history. “Turkey accepted Jewish refugees without question back then. But they could also have been Zen Buddhists,” Schild explains. “The Turks didn’t really do it out of friendliness towards Jews.”

Alongside Jews, other intellectuals persecuted under Hitler were also accepted by Turkey. They included Social Democrat Ernst Reuter, architect Bruno Taut and composer Paul Hindemith.

Turkeyalso worked with specialists and academics which supported the National Socialist regime – and there were more of them than there were persecuted émigrés.

But it is also a fact that Turkish politicians campaigned on behalf of the imprisoned relatives of professors living in exile, securing their release from concentration camps.

Nazis in Istanbul

It is a contradictory image, reflective of the political circumstances of the period. During the Second World War, Turkey declared itself officially neutral. But its historic ties to Germany, both economic and militaristic, were strong.

Starting in 1933, there was even a local branch of Hitler’s National Socialist Party (NSDAP) in Istanbul. It was tolerated by the Turkish government, even though all political activity outside of the ruling Republican People’s Party (CHP), the party of the state’s founder Ataturk, was officially forbidden.

Izzet remembers the anti-Semitic tendencies in daily life. “They spilled over here from Germany. If they wanted to make somebody laugh, they would tell a joke about Jews,” he recalls. “How the Jews were bad people, miserly business people or thieves. We grew accustomed to it.”

Harmony and sunshine?

However, the intake of Jews was romanticized on the Turkish and Jewish side. Turkey had been an important place of refuge for centuries.

In 1492, Catholic kings expelled all Jews from Spain. Many of them immigrated to the Ottoman Empire. Sultan Beyazid II declared them welcome. This historic act shapes the image of legendary tolerance for Jews to this day.

“It was a time of harmony and sunshine for the Jews who lived in the Ottoman Empire and in the Turkish Republic,” says Naim Güleryüz, curator of the Jewish Museum Istanbul and founder of the 500 Years Foundation, which was established in order to honor the historic date.

But not everything was rosy in Turkey during World War II. That is evident, for example, in the drastic special tax affecting above all non-Muslims which was effectively used to dispossess countless Jewish families between 1942 and 1944.

Even renowned professors living in exile feared that if they were denaturalized as German citizens they would be stripped of their work permits in Turkey.

Few traces

The émigré academics heavily influenced intellectual life in the young republic, but there are few traces of that Jewish community in Istanbul today.

“During my childhood we didn’t really know anything about them,” says Robert Schild. “An exception was what my father told me back then. As a young businessman, he had his business close to the university. Now and then he went to lectures by these professors.”

After the fall of the National Socialist regime, the majority returned to their home countries.

Ordinary citizens

Today, the Jewish community consists mostly of Sephardic Jews, ancestors of the Spanish Jews who fled to the Ottoman Empire. There are also a few Ashkenazis – Jews from German-speaking regions or Eastern Europe – who still live in Istanbul. But the 20,000-strong community is shrinking.

Solidarity, however, is increasing. “As a consequence of belonging to the religion and tradition, a Turkish Jew thinks differently from a Turkish Muslim,” says Robert Schild, but adds that “we feel like ordinary Turkish and Istanbul citizens.”

‘We love this country’

And that feeling remains despite the devastating attacks that were carried out on synagogues in Istanbul in 1986 and 2003. Here, everyone emphasizes that Palestinians or Al-Qaidi were behind the attacks, not their Muslim neighbors.

It was a shock, nevertheless. Today, one can only enter the synagogues under tight security regulations. “You just have to live with it – and hope that it doesn’t affect you,” says Izzet Keribar.

He can now reflect on 76 years in Istanbul. “I can assure you that I’ve had a wonderful life, even though we sometimes felt that we didn’t have the same roots as most of the other people here. There were no concentration camps in Turkey. We love this country and are very happy to be here.”

As a photographer with an international career, he could have settled elsewhere, but the thought never even crossed his mind: “I was born here, I have spent my life here, I will also spend the rest of my days in Turkey.”

Source: dw.de