The church was built in the centre of Ohrid’s old town, upon the foundations of an old Christian structure. During Tsar Samuel’s reign (976-1 OU) it served as the cathedral temple of the Church that had a patriarchal status. The building was reconstructed in the time of the Ohrid Archbishop Leo (1037-1056), when its broad stone dome and marble altar screen were built. The latter is among the oldest in the Eastern Christian world. The intensive construction activities undertaken in the early Uth century defined the church’s luxurious appearance marked by its interior and exterior two-storey narthexes. Its west façade has been compared to that of Halke Palace in Ravenna, also known as the residence of Emperor Justinian I.

View Byzantine heritage in the Republic of Macedonia in a larger map

The church’s earliest wall paintings were devised and commissioned by the Ohrid Archbishop Leo, who, being the leading theological erudite, was a negotiator plenipotentiary on behalf of the Ecumenical Church in the doctrinal and theological dispute with Rome in the years of tension preceding the Schism (1054). In the years around 104-5, Leo visually materialised his erudition by sponsoring a unified ensemble which would be a visual argument in support of his theses about the Eastern Orthodox universalism under the patronage of Constantinople. Hence, the first zone of the church was painted with images of the most prominent superiors of the Christian churches. Placed in specifically designated positions, the archpriests illustrated the idea of the hierarchy of the church capitals throughout the Christian world. Places of honour were awarded to the bishops of the (Ecumenical) Church of Constantinople, and the churches of Jerusalem, Alexandria and Antioch, whereas the Church of Rome, included in the basic Christian institutional system, was represented in the diaconicon through the portraits of the six popes. Along with the bishops of Cyprus, the images of St. Cyril of Salonika and St. Clement of Ohrid were added to the composition at the end of this gallery in testimony of the ecumenical status of the Ohrid Church Cathedra. Both representations of these saints are the oldest preserved in Byzantine art. The gallery of the prelates in St. Sophia is the most populous ever painted, and includes the group of popes, while the portrait of Pope Innocent is unique in fresco painting. The highly selective list of thematic and iconographie exclusives in this ensemble also includes a unique scene of the Liturgy of St. Basil the Great, the scene of Abraham’s Sacrifice, whose narrative quality remains unsurpassed, Christ’s blessing of the unleavened Eucharist in the scene of the Apostles’ Holly Communion, the gallery of female saints in the narthex, including the representation of the Mother of God sitting erect on a pillow on the floor. The representation of the Mother of God with her son on the north column in the naos is exceptional in that it shows Christ’s bare feet, which were to be observed in Western painting as late as the 13th century and whose depiction has been interpreted as the germ of the idea of humanising Christ’s divine figure and image.

The prothesis, dedicated to the Forty Martyrs of Sebaste, contains one of the most extensive Byzantine cycles illustrating their lives from their conversion to Christianity to their massacre. Their group representation as canonised saints, with features of their martyrdom, is the only known painting of this kind in Byzantine art. The entire south part of the sanctuary, called deaconicon, is decorated with scenes from the life of St. John the Baptist and was most probably a chapel dedicated to him, serving as a baptistery. This largest 11th century fresco-ensemble in Europe – dark and sombre, expressive and mystical, analytical and stern – is a negation of the earthly and the banal, of the corporeal and the material, of beauty. The messages this painting style sends are the summit of monastic aesthetics and an expression of “ascetic” surrealism in art.

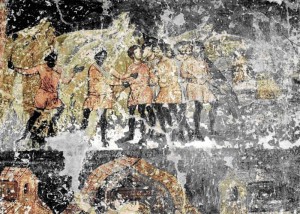

Important painting work also took place in the 14th century, in the time of Archbishop Nicholas. During that period, the walls in the upper storeys of the church’s extensions became inviting painting canvases. The small church to the north of the upper storey of the narthex was the first to be decorated between 134-7 and 1350. Its donor, despot John Oliver, had dedicated it to his namesake saint, St. John the Baptist. The walls were painted with scenes from the patron’s life, while the lower zone was decorated with the images of the members of the donor’s family, who are also significant due to their historical importance. The painting style employed is illustrative of the echoes that Byzantine Renaissance had in the 14th century and eloquently speaks of the talent of its author, the painter Constantine.

The upper storey of the narthex was fresco painted around 1345, owing to a donation from the Archbishop of Ohrid, Nicholas. As befits a cathedral church, this space is dominated by the cycle of the Ecumenical Synods. One of the most important fresco painters in the Balkans and teacher of numerous generations of fresco painters in Ohrid, the painter John Theorian, left his signature on Archangel Michael’s sword in the scene of King David in Penitence. It was precisely Theorian’s disciples who produced the rare painting programme on the upper storey of the exonarthex, also known as Gregory’s Gallery. Under the patronage of the same archbishop, the scenes of the Last Judgment, the Legend of Joseph from the Old Testament and the Act of the Separation of Souland Bodywere illustrated around 1355.

The cycle of Joseph, depicted in forty scenes, was illustrated so extensively only in one other place in the middle ages -St. Mark’s Church in Venice. This scene of the posthumous separation of soul and body, along with the accordingly entitled cycle in St. George’s Church (13th century) of the Hilandar Monastery on Mount Athos, is the only remaining depiction of the monastic-mystical saga in Byzantine art. The magnificent fresco painting in the cathedral of the Ohrid Archbishopric is a unique textbook on mediaeval art between the 11th and the 14th centuries. Here, as in few other places in the Slavonic-Byzantine universe, painted and painted over continuously through the centuries, these fresco-murals are a stratigraphy of superior European achievements in fine arts.

Bibliography:

Serafimova A., St. Sophia in Ohrid, Christian monuments, Cultural heritage protection office, Skopje 2009, 200-205.