Little did I know that one my favourite piazzas in Romania was hiding a secret beneath its modern European facade. I’d heard rumours that Piata Libertati (Liberty Square) in the city of Timisoara was the site of a magnificent Turkish bath during the Ottoman era (1552-1716). But I’d never seen any sign of that world other than a small plaque with Arabic writing on the wall of a nearby building. Then in September 2014 I returned to the city on Romania’s western frontier and discovered something exciting: archaeologists had unearthed the 400-year-old bathhouse known as the Grand Hammam.

Excavations were still underway but I could not wait to explore the treasures that had been uncovered. I started asking around and learned that archaeologists had found more than just the Turkish bathhouse. Crews were digging in several areas of the historic centre, and the city’s Oriental past was literally emerging from the ground. I was downright giddy. It’s exciting to witness a city that you have come to know intimately reveal an entirely new facade and a new set of places to explore. It felt like time travel.

Timisoara was conquered by the Ottoman Empire in July 1552. Under the command of Albanian-born Kara Ahmed Pasha, an army of roughly 16,000 men took the city and soon transformed it into the capital of the Banat region. For more than 160 years, Timisoara was controlled directly by the sultan. The city was on the forefront of the Ottoman and Austro-Hungarian struggle for territory that would shape the region for centuries to come.

Standing in the Grand Hammam excavation area, I could see the ruins of ancient chamber areas and air circulation passages that were slowly being restored. I thought of the dozens of times I had visited Piata Libertati completely unaware of what lay below. The piazza is centrally located between Piata Unirii (Union Square), a popular meeting spot with bars and cafes, and Piata Operei (Opera Square), which hosts some of the city’s most important community and cultural activities. The two buzzing squares make Piata Libertati feel like an oasis of relative calm, its trees offering shade to anyone who cares to sit and watch life sweep past.

Back in the 17th Century, the piazza must have been an ideal spot for people watching, too. Turkish baths in various parts of the world continue to be more than just places for bathing and relaxation. They play a part in civic life by bringing people together in such an intimate setting, as well as a religious role in purifying the soul. The excavations at Piata Libertati revealed that the Grand Hammam contained 15 rooms arranged around a large central hall. The floor of the baths was suspended on brick pilasters – square columns – to allow the circulation of hot air, which was produced in an oven chamber. Each room was equipped with air passages and smoke chimneys. Outside, the area was surrounded by gardens and interior courts of nearby buildings, creating an atmosphere that was private and calming, and ideal for conversation.

Standing at the piazza on a chilly spring morning during an earlier visit, I wished the hammam was still there so I could warm up in its steamy interior. I wanted to explore the ruins that are changing the face of the city further, so I strolled over to Piata Sf Gheorghe (St George Square), less than 100m to the west. The piazza is a small square tucked between Viennese-style buildings. During previous visits to Timisoara, I’d often passed by it on my way to grab a snack at one of city’s covrigi (pretzel) shops, pausing along the way to flick through the English-language books for sale on makeshift bookshelves.

But important discoveries have recently been made in Piata Sf Gheorghe, too, leading Romanian archaeologist Florin Drasovean to proclaim the spot “the world of the gods, the world of the living and the dead world”.

In the first half of the 18th Century, Captain François Perette with the Imperial Austrian military, drew up a map of Timisoara on which he marked several key landmarks from the Ottoman period. One of the most important was the Grand Mosque of Timisoara. Evliya Celebi (1611-1682), a renowned travel writer from the Ottoman period, described the mosque in his journal as a “great sanctuary for prayer”. After the Austrian conquest in 1716, the mosque was transformed into a Christian church and later demolished. A new church built on the site erased nearly all signs of the mosque – until 2014 excavations . After centuries in absentia, the mosque’s foundation and artefacts from the period are finally emerging, allowing Drasovean to rediscover “the world of the gods”.

And that’s not all. In addition to the mosque, archaeologists digging in Piata Sf Gheorghe have uncovered the remains of wooden houses and aqueducts. The aqueducts were among the first urban water management systems to be constructed in Romania. While the Turks did not originally build them, they did organise them to supply water to public buildings. The wooden houses date back to the medieval period before the Turks arrived and were maintained until the Austrians began to modernise the city in the 18th Century. Archaeologists have also excavated 160 graves around the mosque, most containing commoners who were wrapped in a single piece of cloth in accordance with Islamic tradition.

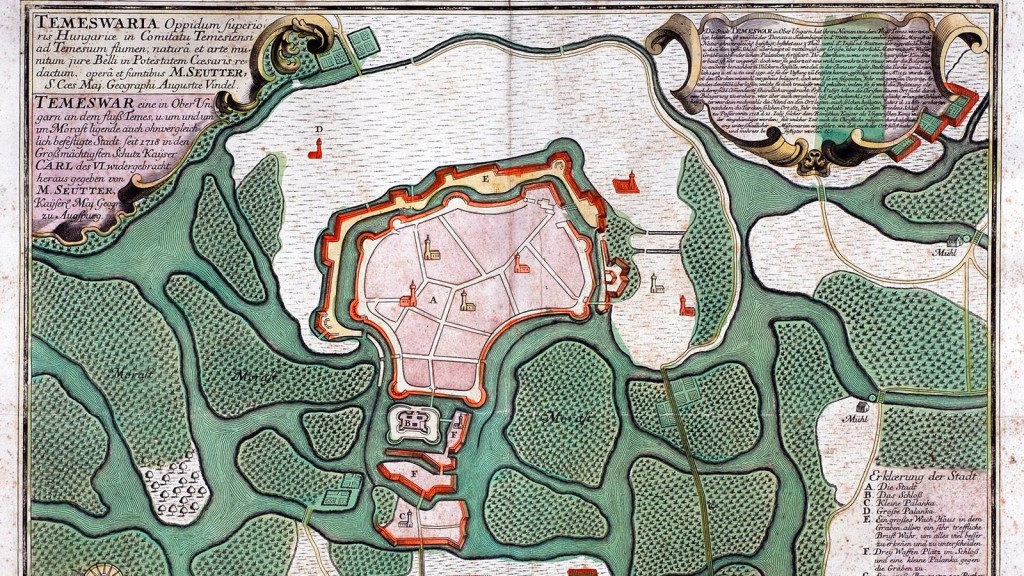

To maintain peace and political control during the Ottoman period, the Turks accepted people of all faiths and ethnicities and did not interfere in locals’ lives. While this kept Timisoara safe from within, the city still faced threats from the outside. So the Turks reinforced the city’s defences. Taking advantage of the nearby rivers of Bega and Timis, the Turks created moats around the city, as well as a fortress. Towering above the water were walls up to 3m thick, guarded by Ottoman soldiers. The defences of Timisoara were so effective that when the army of Eugene of Savoy did conquer the city in 1716, it was because the Turks surrendered following a long siege and unusually bad weather.

Archaeologists believe their recent discoveries are just the beginning. Timisoara’s history dates back to antiquity and many secrets have yet to be unearthed – giving all of us yet another good reason to visit the inviting piazzas of Timisoara.

Source: bbc.com